Food Systems and the Stability of States

A Brief Historical Record

Throughout history, states and empires have rarely collapsed without warning. More often, they weakened quietly as core systems lost resilience. Among the most consistent, and underestimated, of these systems has been food production and provisioning.

Food system fragility does not usually cause immediate collapse. Instead, it erodes legitimacy, concentrates risk and amplifies shocks until political stability becomes impossible to sustain.

The historical record is unambiguous.

Centralization Without Resilience: The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire relied on a highly centralized grain supply to feed its urban population, particularly Rome itself. Over time, smallholder agriculture declined and was replaced by large estates and long-distance provisioning from North Africa and Egypt.

This system functioned efficiently; until it didn’t.

When climate stress, conflict, and territorial loss disrupted grain routes, food shortages quickly translated into urban unrest, political instability, and military overextension. The problem was not a single famine, but the loss of redundancy and local resilience.

Takeaway: Centralized efficiency without buffering capacity creates chronic political vulnerability.

Roman bakery and grain distribution scene (1st century CE). Urban provisioning depended on long-distance grain shipments from Egypt and North Africa.

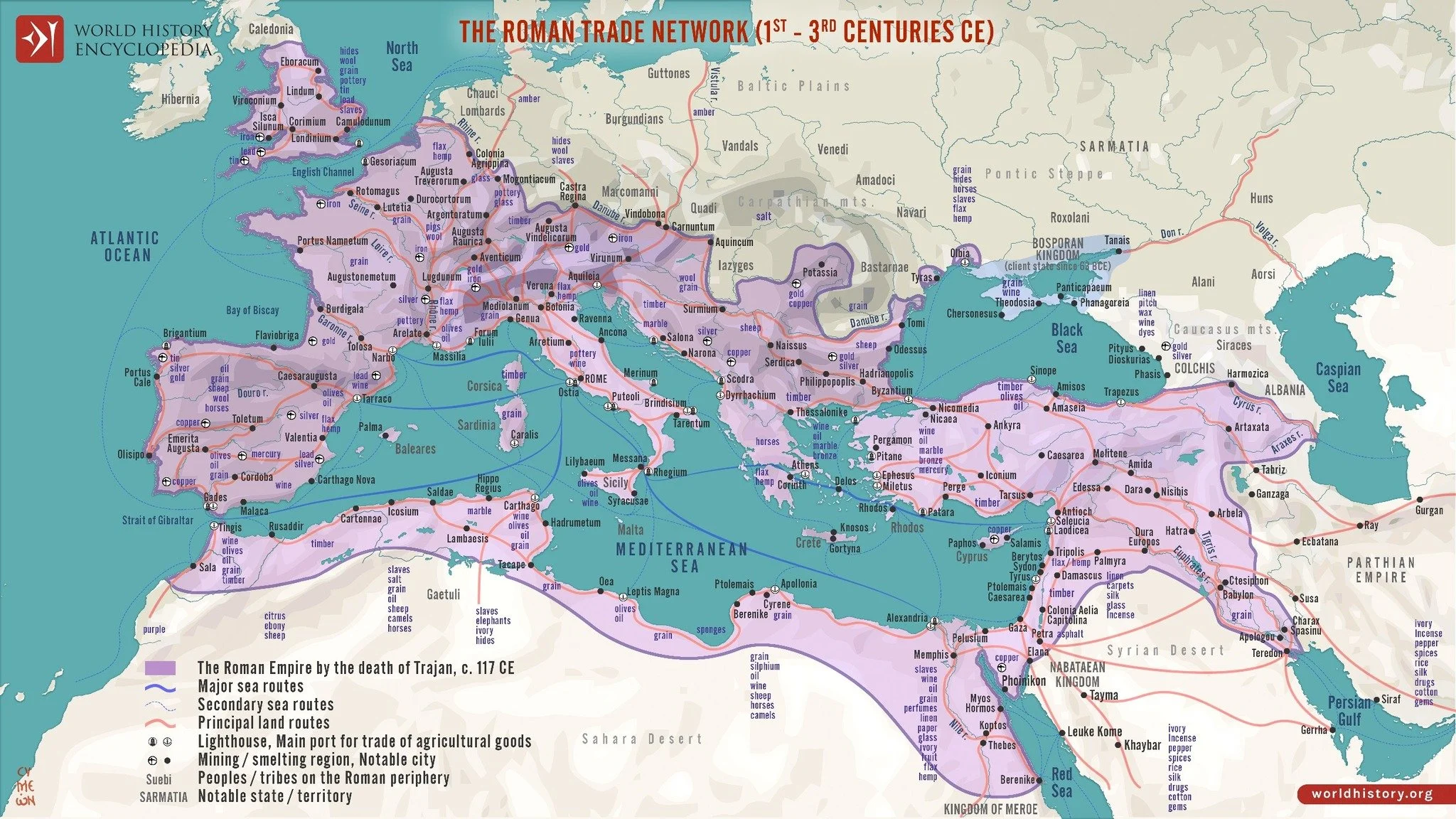

Mediterranean grain supply routes under the Roman Empire. Rome’s urban population depended heavily on long-distance shipments from Egypt and North Africa, creating a highly efficient but fragile provisioning system.

The Long Interlude: Hunger Was Endemic, Fragmented and Endured

With the breakdown of Roman logistics and state provisioning, much of Europe reverted to localized agrarian systems characterized by low surplus, limited storage, and minimal buffering against shocks. Crop failures, weather variability, disease, and conflict produced recurring famine conditions across regions and generations. Hunger was not episodic—it was a recurring feature of life.

This period was not stable, nor was it resilient in any modern sense. It was brutal. Malnutrition was common, life expectancy was low, and famine periodically erased entire communities. What distinguished this era was not the absence of food system failure, but the absence of institutional mechanisms capable of responding at scale. Food insecurity was normalized, localized, and largely invisible to centralized authority.

Because deprivation was fragmented and endured privately—by households, villages, and regions—it rarely crystallized into a single political crisis capable of challenging state legitimacy. Suffering was real and severe, but it was not structurally legible as a system-wide failure requiring coordinated intervention.

Only later, as governance, markets, and expectations re-converged at larger scales, did food insecurity once again become a politically destabilizing force.

Takeaway: The Long Interlude shows that civilization doesn’t collapse all at once; instead hardship accumulates, safeguards disappear, deprivation becomes normal and instability is no longer recognized as failure but accepted as life.

After the collapse of Roman provisioning, Europe experienced centuries of persistent food insecurity marked by localized production, repeated famine, and chronic deprivation; suffering that was widespread, severe, and largely borne privately rather than addressed as a systemic public failure.

Price Volatility and Legitimacy: Ancien Régime France

In 18th-century France, bread consumed the majority of household income for much of the population. Food security was not abstract; it was daily arithmetic. When bread prices rose, families skipped meals immediately.

Late in the Ancien Régime, grain market liberalization, combined with poor harvests, hoarding, and speculation, produced sharp price volatility. Grain often remained available, but at prices many could not afford. Hunger spread not because food vanished but because access collapsed.

The French state retained formal authority but it lost moral legitimacy when it could no longer guarantee affordable bread. Longstanding expectations that the crown would intervene in times of scarcity went unmet. What had once been tolerated hardship was reinterpreted as neglect.

Bread riots erupted across cities and market towns. Protest quickly escalated into mass mobilization, not around political theory, but around survival and perceived indifference. Revolutionary ideology followed hunger; it did not precede it.

Takeaway: Food price instability delegitimizes authority faster than abstract injustice. When staple foods become unaffordable, political order unravels quickly.

Grain markets and bread provisioning in 18th-century France. Price volatility and supply disruptions directly undermined political legitimacy in urban centers.

Administrative Decay and Scale Pressure: The Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty governed one of the most sophisticated agrarian systems in the pre-industrial world. State-maintained granaries, irrigation works, and famine relief mechanisms were designed to stabilize food supply across vast regions and buffer local shocks.

For a time, the system worked.

Over the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, however, population growth steadily outpaced agricultural resilience. Land was subdivided, marginal soils were brought into production, and ecological buffers narrowed. At the same time, administrative corruption and fiscal strain weakened the granary system and disrupted famine relief.

Local crop failures increasingly cascaded into regional and national crises. What had once been absorbed by surplus and coordination now overwhelmed the system. As food insecurity spread, peasant uprisings multiplied, relief failed to arrive on time and central authority eroded.

The Qing collapse was not caused by a single famine or shock, but by scale pressure: the mismatch between the demands placed on the food system and the state’s declining capacity to manage them.

Takeaway: Even capable states fail when food resilience degrades faster than institutional capacity.

Irrigated agriculture during the Qing Dynasty. State-supported irrigation and intensive labor sustained food production as population growth placed increasing strain on land, water, and administrative capacity.

Extraction Without Reinvestment: The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire governed a vast agrarian system supplying cities, armies and imperial administration through grain requisitioning and tax farming. Over time, extraction increased while reinvestment in agricultural resilience declined.

Fiscal systems such as tax farming (iltizam) prioritized short-term revenue over soil health, irrigation, storage, and local buffering capacity. Surplus was removed, but the conditions that produced it were not sustained. Rural communities absorbed the losses first: declining yields, peasant flight, malnutrition, and recurring subsistence crises became common.

Climate volatility during the Little Ice Age intensified these pressures. As harvests failed more frequently, extraction continued, hollowing out rural capacity. Cities and imperial institutions remained provisioned longer, but increasingly through coercion rather than resilience.

The system did not collapse suddenly. It thinned. By the time food insecurity and instability became acute in urban centers and military supply, the rural systems that once absorbed shocks had already been exhausted.

Takeaway Food systems that extract surplus without reinvesting in resilience do not fail quickly. They hollow out, leaving states increasingly brittle and dependent on force rather than capacity.

Ottoman administrative authority under the iltizam system. Revenue extraction was institutionalized, while reinvestment in rural resilience eroded.

Masked Fragility: The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union maintained the appearance of food security through centralized planning, price controls and state distribution. For decades, urban populations experienced predictable access to staple foods, reinforcing the perception of system stability.

Beneath that surface, however, agricultural productivity remained structurally weak. Collective farming reduced incentives, soil health deteriorated and local resilience declined. Rather than repairing these weaknesses, the state increasingly relied on imports, subsidies and administrative controls to mask failure.

Grain imports, particularly from the United States and Canada, became essential to sustaining urban provisioning. Price signals were suppressed, shortages were managed administratively and inefficiencies were absorbed by the state. To consumers, shelves often appeared stocked; to planners, the system was increasingly brittle.

When fiscal pressure mounted and foreign exchange tightened, the masking mechanisms failed. Shortages became visible, queues lengthened and public trust collapsed rapidly. The system did not unravel because food suddenly vanished, but because the state could no longer compensate for decades of accumulated fragility.

The Soviet case illustrates a distinct failure mode: food systems can remain politically stable as long as failure is hidden, subsidized or externalized, but once masking fails, legitimacy collapses quickly.

Takeaway: Food systems that rely on concealment rather than resilience do not decline gradually. They appear stable until the moment they cannot.

State-managed grain production in the Soviet Union. Central planning and mechanization sustained the appearance of abundance even as agricultural resilience declined.

Late Soviet bread lines. Food insecurity did not arrive suddenly; it surfaced when the state could no longer conceal accumulated fragility.

A Pattern, Not an Anomaly

Across eras, geographies, and political systems, the pattern is consistent. States do not usually fail because food disappears. They fail because resilience erodes, risk concentrates, and legitimacy collapses when systems can no longer absorb shock.

Sometimes failure is driven by centralization without redundancy.

Sometimes by extraction without reinvestment.

Sometimes by price volatility, scale pressure, or concealment.

The mechanism varies. The outcome does not.

Food systems rarely trigger immediate collapse. They instead shape the conditions under which collapse becomes inevitable: by normalizing hardship, masking fragility, or quietly transferring risk onto households and communities least able to bear it.

History does not suggest that modern societies are exempt from these dynamics, only that their failure modes may be harder to see and easier to rationalize, until they are no longer containable.